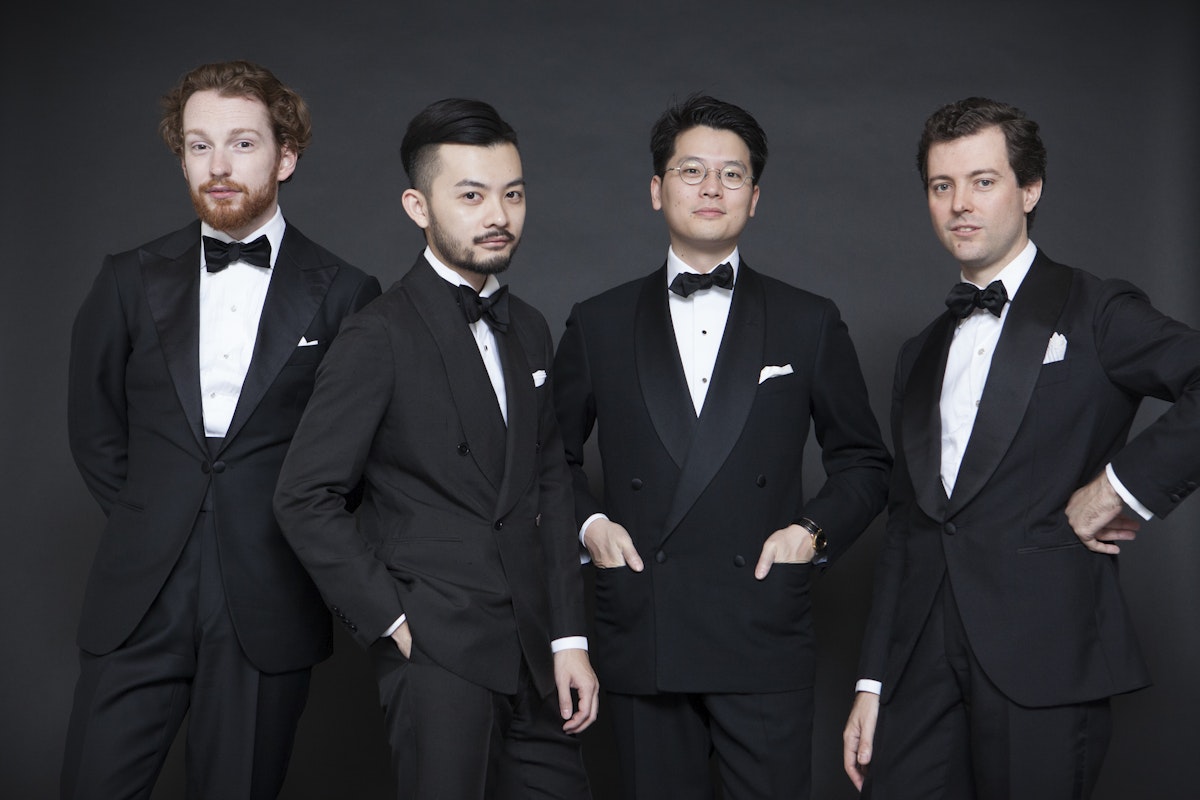

Menswear authority, writer, editor and friend of The Armoury, Bruce Boyer, lends his thoughts on the art of black tie.

A point should be made at the outset that this discussion isn’t written on stone tablets, it’s more just a jaunt through classic evening dress, fully understanding that options are numerous, personalities myriad, and occasions countless. The point of this particular discussion is that the past decade or two has seen considerable confusion among men concerning what to wear for occasions that used to merely prescribe “Black Tie”. It used to be so easy, but my feeling now is that many men, who would prefer traditional dress, feel cast adrift in a sea of options that cater to the trend of "Creative Evening Clothes". This doesn’t mean you can’t wear whatever you want to the party, we’re simply talking about the nicest and easiest way to dress for upscale holiday entertaining. That is, if you know what you’re doing, but more about that in a paragraph or three.

Ever since it entered the gentlemanly wardrobe in the 1880s, tuxedo styling has more or less followed business suit styling. If suits have wide shoulders or favor double-breasted closures let’s say, tuxedo styling will follow their lead, which should make buying a tux pretty simple. There are, however, subtle differences to recognize. While a day suit may have all sorts of details—extra pockets and flaps, swelled edges, a variety of vents, cuffs and such—elegant understatement and simplicity of cut are the hallmarks of true black-tie dressing. The tuxedo jacket and trousers are not to be considered a storeroom for pens and notebooks, loose change, mobile phones and other tech devices and the like, any more than an evening dress watch should tell anything other than the time.

Single-breasted dinner jackets usually take only a single-button closure (rather than the two, three, or more that day jackets may take); double-breasted jackets usually take a 2X4 closure. Both styles are classically ventless in back and cut close to the hips to provide a slimming, elegant line. And lapels are never notched: both single-breasted and double-breasted take either peak or shawl lapels, the choice being a matter of personal preference. Lapels themselves are faced, i.e. covered with satin or grosgrain which usually matches the color of the jacket itself. The two side pockets are simple self-edged, straight slits (called jetted pockets) without flaps, and a welted chest pocket.

Dress trousers are cut from the same fabric as the jacket, and differ from day trousers in two important respects: evening trousers are never cuffed regardless of current fashion; and there is a stripe running down the full length of the outer seam of the same fabric used for the jacket facings. Belts are not worn with dress trousers, braces (suspenders) are favored. The trouser waistband itself may be covered with a cummerbund or evening waistcoat. Again, no flaps on any pockets. Minimalism is the goal, discretion the key.

Before we consider the accompaniments to the tuxedo, there’s a possible third piece to mention, the waistcoat. Dress waistcoats are a complete matter of fashion and personal preference, are cut lower than day waistcoats—often with a horseshoe-shaped front—usually only have three or four buttons, and can be backless for added lightness. The alternatives to the waistcoat are either some sort of finished trouser top or a cummerbund. The word derives from the Hindi kamarband, meaning sash (in the sense of waistband), and this formal accessory became popular in England after 1890 as part of the legacy of the British in India. The cummerbund is usually made of the same facing fabric and is worn (this question always comes along) with the pleats open to the top because it was originally a good place to put theater tickets, loose change, a cigar cutter, a pill case or other small items. Even today, bespoke cummerbunds will have small pockets inserted into the pleats for this purpose.

A quick note about dress fabrics. Classic evening dress calls for simplicity, elegance, and comfort, so a lightweight, clear-finished black or midnight blue cloth is what’s wanted. Cashmeres, linens, cottons, nubby shantung, twills, and even denims have been used to striking effect, and are not beyond the pale. They’re merely eccentric (as would, for example, patch pockets on the dinner jacket). Formal cloth is characterized by a smooth finish, low luster, and avoidance of pattern. Light-weight worsteds, mohair or silk blends, baratheas, and even plain-finished broadcloths are considered traditionally more in keeping with the goal of elegant simplicity.

Evening shirts are either fine cotton (like voile or Marcella pique), lightweight linen (like Italian), or lightweight silk (also Italian), and always white (unless the wearer is intent on making some sort of assertion). They always have turn-back (French) cuffs like any fine business shirt, but usually have a pleated bosom (The Rule: the larger the man, the wider the pleats). Collars are either simple turn-down and soft, or standing wing (The Other Rule: the collar points go behind the bow tie). The classic formal shirt has three or four middle sets of buttonholes, for which studs matching the cuff links replace the buttons. Colored formal shirts, or those with ruffles, lace, piping, or other design additions are considered both unnecessary and unwanted.

A quick note about jewelry. Since minimalism is a goal in classic evening dress, a stud and cuff link set, a small and discreet dress wristwatch, and personal ring are all that’s called for. When it comes to men’s jewelry, statements are made with fineness, rather than size.

The most important accessory is the tie. Although we’ve all seen a variety of celebrities wearing four-in-hand neckwear with tuxedos, this fashion isn’t only now so old it should be carbon-dated, it relinquishes the opportunity to wear something different for an occasion. The bow—usually matching the same material as the facings—may be either small or large, square-ended or pointed. Some men are unaccountably fearful of tying a bow tie and opt for a pre-tied one. But a bow is a bow is a bow: a short practice run will do the trick, and remember that it shouldn’t look too perfect, a perfectly tied bow is the sure sign of the amateur or histrionic.

The whole point of traditional evening wear is, once you know the form, you can look elegantly understated, comfortable, and confident without much bother.

There’s little to be said about evening footwear—worn with plain black or midnight blue socks in fine cotton, merino wool, or silk—except that it should be lightweight, thin-soled, usually black, and unadorned. This isn’t only because of aesthetic considerations, but, as with the rest of the outfit, eveningwear has always been associated with dancing and entertainment. There’s a surprising variety of acceptable footwear: velvet Albert slippers (with or without decoration), patent leather pumps or oxfords, or plain black calf opera slippers (with or without a bow).

As for the other minor additions to the outfit—boutonniere, pocket handkerchief, scarf, and outerwear—there are dozens of advice manuals out there prescribing one item or another. All of these books are of course invariably out of date almost before they reach the shelves. Today things move and change at a rate where the laying down of precise rules is one of the more thankless jobs around.

There’s one bit of advice though that you won’t find in these self-help tomes that’s worth passing along. And it refers to wearing clothes in general: the meaning of clothes, like the meaning of words, depends on usage.The whole point of traditional eveningwear is, once you know the form, you can look elegantly understated, comfortable, and confident without much bother. The trick about clothes is to wear them like you mean it, and the best way to do that is to relax and give the assured impression that it’s simply a natural grace.